A very rare Chinese saber guard dating from the height of the Qing dynasty.

62 x 28 x 29 cm

3998 grams

Iron, silver, gold, wood, leather, rawhide.

Eastern Tibet or China.

17th century

Introduction

Saddles with pierced iron plates, richly damascened in gold and silver, were popular among the elites of Tibet, Mongolia, and China. The work originated from Tibet and was in turn inspired by Persian pierced metalwork.1

Later, the production also took place in China. In fact, the pierced ironwork in the Tibetan style became a staple of the imperial armorers in Beijing in the early Ming dynasty and saw a revival during the Qing period. The work consisted of fine saddles, belt fittings, mounts for sabers, bowcases, and quivers. Especially the saddles seem to have been popular diplomatic gifts between wealthy Chinese, Manchus, Tibetans and Mongols.

After the passing of Qing emperor Hong Taiji in the year 1643 for example, various Mongol tribes sent tribute missions to the Qing court in order to pay their respects. Among the tribute were various items including -but not limited to- pelts, feathers, rosary beads, bolts of Chinese and Japanese silk, silk brocade, camels, and horses. The majority of those horses were presented without a saddle but some were specifically mentioned as having "carved saddles" and "lacquered saddles", perhaps alluding to the quality of these horses as well.2

Some of the saber guards in Tibetan style made it to Japan as well, where they inspired a genre of nanban tsuba.

Notes to introduction

1. John Clarke; A History of Ironworking in Tibet: Centers of Production, Styles, and Techniques. Published in: Donald Larocca; Warriors of the Himalayas, Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Yale University Press, New Haven and London. Pages 21 - 33.

2. Nicola Di Cosmo & Dalizhabu Bao; Manchu-Mongol Relations on the Eve of the Qing Conquest. Brill, Leiden, 2003. Pages 173-222.

This example

A nice old saddle in an earlier Tibetan pierced iron style. The base is made of six pieces of wood, joined with rawhide. Both pommel and cantle are covered with large pierced iron plates that feature openwork panels containing two facing dragons amongst foliage that are chasing a flaming element, the "triple gem" that contains three jewels representing the Buddha (the fully enlightened one), the Dharma (his teachings) and the Sangha (the monastic order of Buddhism).

On the cantle, the dragons are raised above a base of three stones in the sea, representing a sacred mountain, with above it a mushroom-shaped cloud called a rúyì (如意) or "as you wish". These clouds as a centerpiece are also a common element seen on 17th century Qing imperial sword guards, such as this one.

Pommel and cantle are connected by wooden sideboards, each with an extension that projects forwards and backward. These extensions are each covered with a pierced iron plate, each depicting a running dragon or xíng lóng (行龍) flying over a wavy sea, amongt pointy clouds.

All mounts have a backing of indigo dyed fabric that is applied directly over the wood with the purpose of providing a nice background for the openwork. Backing openwork with fabric in this fashion was also done in Bhutan and Nepal.

Dating & attribution

When it comes to dating, the stylistic elements of the saddle all put the work firmly into the 17th century. Characteristic of this period are the rather bold work with long, narrow tendrils with lots of open space, and the style of the clouds. By the late 17th century this work had already started to become finer and less bold, a trend that would reach its peak under the Qianlong emperor.

The saddle falls into a closely related group that according to Donald Larocca is either of Eastern Tibetan or Chinese origin. Other examples within this group are two saddles, Metropolitan Museum accession numbers 1997.214.1, 1999.318 and a pommel plate in the same museum, accession number 2000.404.1

Another detail I started to notice within this group is that the transition between the pierced plate and the "legs" of the pommel plate follows a certain shape that is also observed on Jinchuan royal swords.3

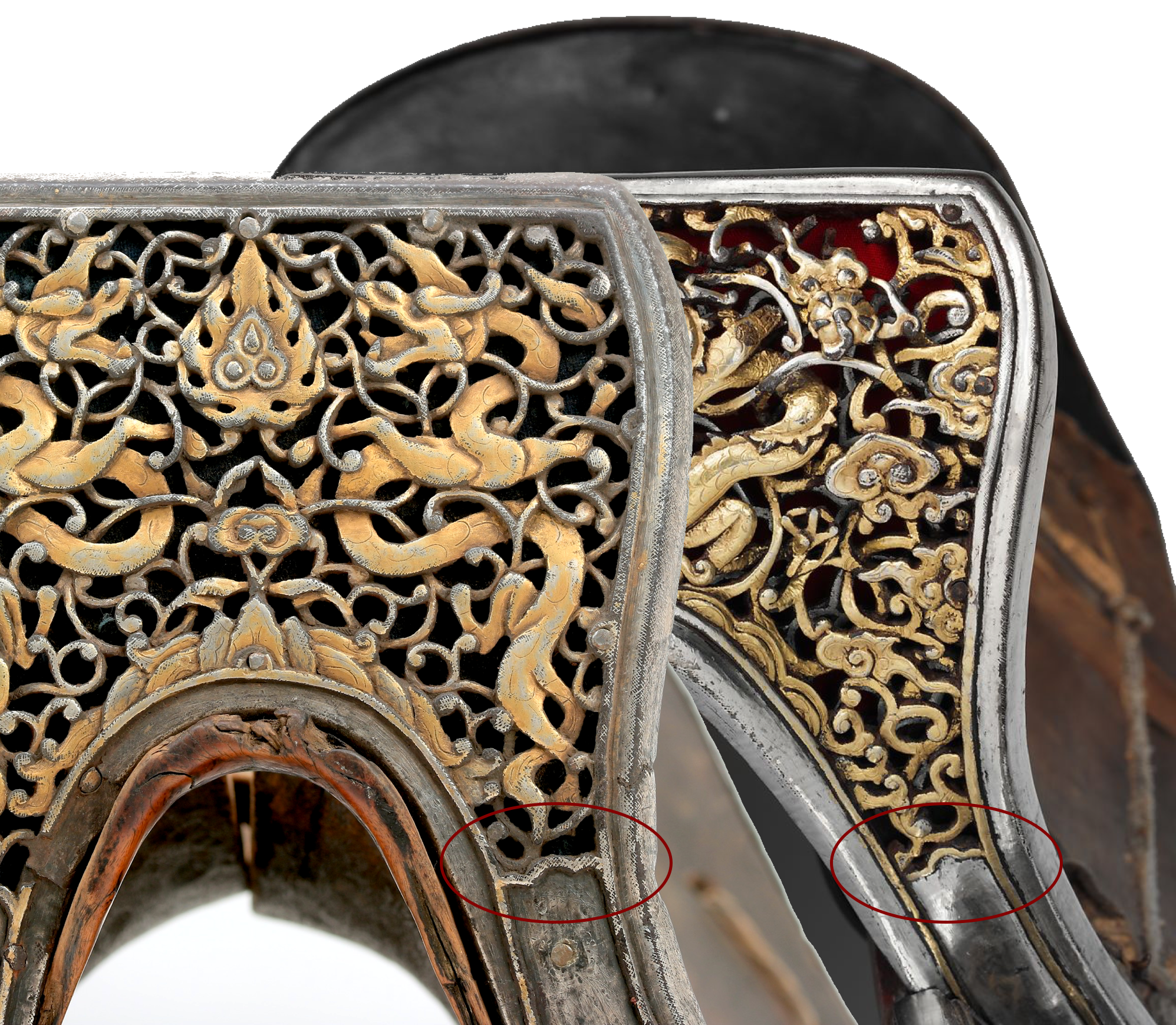

Our saddle (left) imposed on Metropolitan Museum accession number 1997.214.1 (right.)

Notice the areas circled in red.

The Jinchuan Royal Sword I sold in 2017. Notice the shape on the back of the scabbard mounts.

It may seem like a minor detail, but attribution is often about smaller details. An accurate attribution may always stay difficult because skilled craftsmen moved around and we know there were Bhutanese, Nepalese and Tibetan craftsmen working in the Qing workshops as well. That said, I am not used to seeing this exact element anywhere else but on these saddles and this sword. This may strengthen Donald Larocca's hunch that they were made in Eastern Tibet, or perhaps just over the border in Sichuan.

Condition

In decent condition overall. All the woodwork is original to the piece, and of considerable age. The metal plates retain most of their silver, but there is wear especially on the gold. The head of one of the dragon on the side board ends is broken. There is a crack in the left arm of the pommel plate, this is old damage that is repaired by the application of metal strips behind it. It seems a common issue on such plates, we have a Tibetan style pierced saddle plate that was broken in a similar fashion. See photos to get a complete impression of the condition of the various parts.

Conclusion

A rare Tibetan style pierced iron saddle with original wooden saddle structure, retaining all pierced iron plates. The plates in turn retain most of their silver, applied by cold damascening, and some of their gilding, applied by mercury gilding. The overall style of the metalwork places the piece in the 17th century, and it is likely made in either Eastern Tibet or Western China. The flat-top represents a rarer form that is not frequently seen.

Notes

1. For comparisons, see my description of a Chinese openwork guard elsewhere on this site. Its article features sabers that belonged to Hong Taiji (reigned 1636 to 1643) and one that belonged to Kangxi (reigned 1661 to 1722).

2. Donald Larocca; Warriors of the Himalayas, Rediscovering the Arms and Armor of Tibet. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Yale University Press, New Haven and London. Pages 214 - 229.

3. See a rare Jinchuan Royal sword I sold in 2017.

With markings attributing it to the Tongzhou incident and a Japanese surrender tag.

Of classic shape, with a leaf-shaped blade on a socket, connected by a cast bronze base.

A standard pattern Qing military saber, but with the rare addition of a label in Manchu.